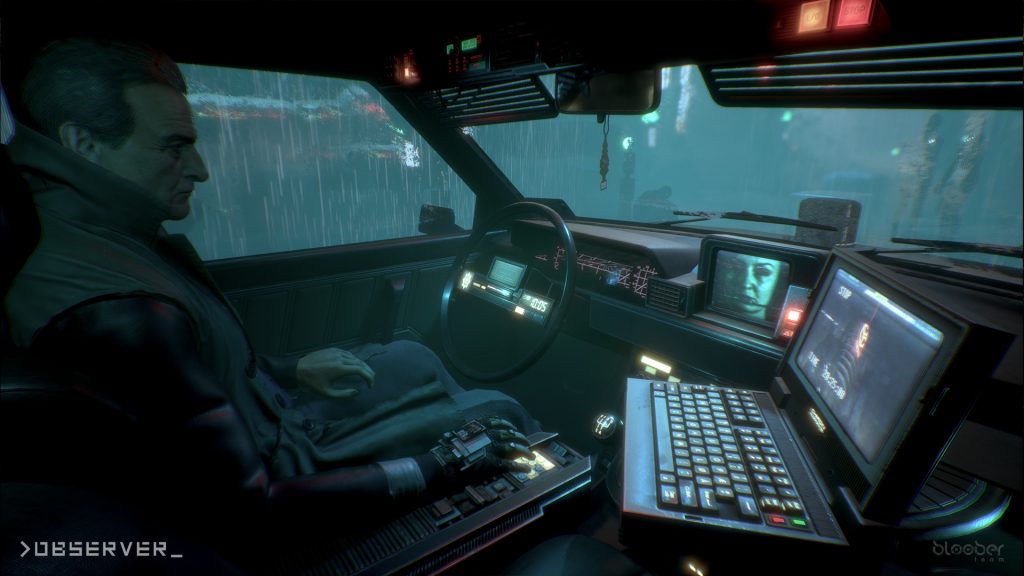

The year is 2084. You sit in the confines of your car, the distinctly 80s sci-fi interior blinking away. Rain falls oppressively from the sky, muting the neon-drenched visage of the urban skyline. The chatter from the police radio scanner drones on in the background. An air freshener hangs from the rearview mirror. You are Dan Lazarski, an Observer given his tired, gravelly inflection by Rutger Hauer, well known for his portrayal of replicant Roy Batty in the 1982 cyberpunk cult classic, Blade Runner. Observers are a special class of cybernetically augmented, corporate-funded police who hack and invade your mind, using your own thoughts, feelings, and memories against you. They are the conceptual meeting point of 1984 and Neuromancer.

At the start of the game, Dan is drawn to a low income tenement by a strange message for help from his estranged son, Adam. Shortly after his arrival, the complex is thrown into a lock down and access to the outside world is cut-off. Trapped, Dan begins to search for his son, unraveling the mystery of the events proceeding the unexpected call for help. This investigation comprises roughly half of the gameplay experience, using augmented vision modes to scan accessible rooms for relevant objects and information and going door to door to interrogate tenants about the events of the proceeding night.

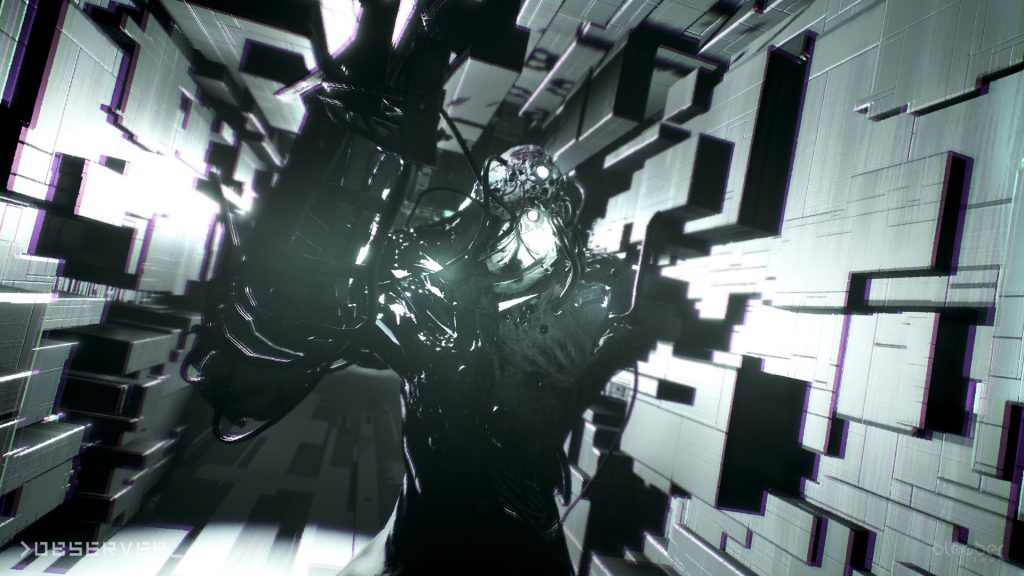

The story takes a turn for the grotesque and the bizarre once circumstances (a string of grisly murders) require you to do what Observers do best: enter the minds of criminals and victims. These mind-hacking sequences are nightmarish patchworks of each character’s history, neuroses, and the circumstances leading to their death or near-death. As the game nears its conclusion, the divisions between these nightmare sequences and reality, as well as between Lazarski himself and his targets, become harder to discern. The surreal intrudes on the real and you begin to lose track of time. What is real? What is a hallucination? What’s a hologram? And from whose deteriorating mind? You can’t trust your perception, especially when the reality of the situation is already strange as it is. Is that a werewolf? It can’t be.

World-building is a major strength for this game. Observer’s environments are overtly inspired by the set designs of Bladerunner. This is a world in which a Polish corporation rose to power unchallenged out of the wreckage of a digital plague called the “nanophage” and a devastating world war. This is not sleek, sterile science fiction. It’s a cohesive embodiment of the “high tech, low life” themes of cyberpunk. The new is built on the old and neither is particularly well-maintained. Holograms, bulky CRT displays, and power cables running along the walls and ceilings cover the run-down, low income “Class C” housing complex that serves as the primary settings of the game. Collapsed walls provide access to new areas almost as frequently as functional doors. Bathrooms are covered in filth.

The characters who occupy its world are similarly run-down. They have cheap, ugly augmentations requiring constant maintenance they can’t afford. Their dependency on stabilizing drugs is effectively a proxy for their subservience to Chiron, the corporation that provided both. Mental illness and substance or VR addiction are commonplace. Complete dysfunction is the norm. They retreat from reality to the safety of their rooms and rarely emerge, communicating with the outside primarily through video intercoms mounted to their doors. It’s a colorful cast of characters, from a couple arguing with their kids, to a lone sex robot that hints to self-awareness.

The protagonist is no exception, unsure what it means to be human in a world in which nearly every part can be replaced and haunted by the death of his wife for which his son still blames him. He is completely dependent on a drug called “synchrozine” to stabilize his cybernetic augmentations. This synchronization constantly degrades, requiring him to take regular doses. This is communicated to the player primarily through digital artifacts which obscure your vision more as Lazarski’s condition worsens. This provides a compelling parallel and foreshadowing to Lazarski’s own mental deterioration as the story continues. Rutger Hauer does a respectable job lending credibility to the character, despite having no other voice acting credits on his resume. His voice simply fits the role so well, I would not be surprised if it was written with him specifically in mind.

The gameplay itself is straight-forward and simple. Scanning the environment with various augmented vision modes for clues and access codes, solving simple puzzles, interrogating tenants, and some stealth sequences account for the majority. There is also a recurring arcade game found on the various computer terminals that you can unlock a level at a time at various points. The game isn’t particularly long, depending on how focused you are on the critical path, but there are several optional side stories to complete and a large number of nanophage patient cards to collect.

All of this works adequately, but it doesn’t stand out. Where >observer_ excels is in creating a convincing sense of space, immersing the player in a dark, surreal, near-future dystopia. The developer on a few occasions opts for cheap jump scares that don’t add much to the experience, but the bulk of the horror is in the persistent, foreboding atmosphere and disturbing (not at all kid-friendly) imagery. Bloober Team manages to successfully cover a broad range of dystopian science fiction themes without fumbling with them. >observer_ is a game with a clear focus on atmosphere and narrative, but it leverages its fairly simple mechanics effectively to that end to create a memorable experience worthy of the cyberpunk and horror genres.

No comments